Surprisingly few writers head into a book-writing journey with a clear outline in mind. Writing a non-fiction book often begins with a flurry of impulsive draft writing. Topics and sections manifest out of order or in loops, sometimes with certain themes and ideas repeating themselves excessively. This is normal.

This spiral-style draft-writing is actually a reflection of how we naturally converse with others. We loop, we repeat; 20 minutes in we expound on the story we shared at the start of the conversation. I tell all my new authors:

Consider your first draft to be an interview with yourself. A good interviewer does not interrupt a story source. She lets that interviewee run with the flow, and she takes notes. Later, she’ll review those notes and bring a sequential order to them. That’s what you do, as an author, when you shift from raw draft-writing to revision work and structural arrangement.

Even writers who are dedicated to detailed outlines at the start, still wind up draft-writing in circular form. They follow their outline perfectly, but at some point, while draft writing Chapter 8, suddenly they think of 3000 words of content that really needs to show up in Chapter 2. It’s inevitable.

Ah, the jumble. You’re officially in the weeds. It’s no fun, but it’s par for the course when writing a book. What do you do once you’ve got a book’s worth of material (60,000 to 90,000 words), but a broken structure or no structure at all?

First, Sort Your Beads

As a child I loved beading bracelets and necklaces. As an adult I freely admit I have no inherent talent for jewelry making! But I like the overlaps between beadwork and writing craft. Each section and rough draft chapter is a bead. Some beads are larger and more ornate than others. Some are small—perhaps bulleted lists of statistics. These fragmented blurbs are like tiny red beads that probably need to be rationed out through the whole book.

For instance, you probably don’t want all your hard statistics pooled in Chapter 1. That would be like placing all the red beads at one end of necklace. It’s more visually pleasing to establish a rhythm for the various types of content and distribute each type of “bead” with a sense of order.

Your job now is to sort all the content blocks you’ve generated. Then begin to arrange and distribute those sections and fragments.

Arrange the Beads

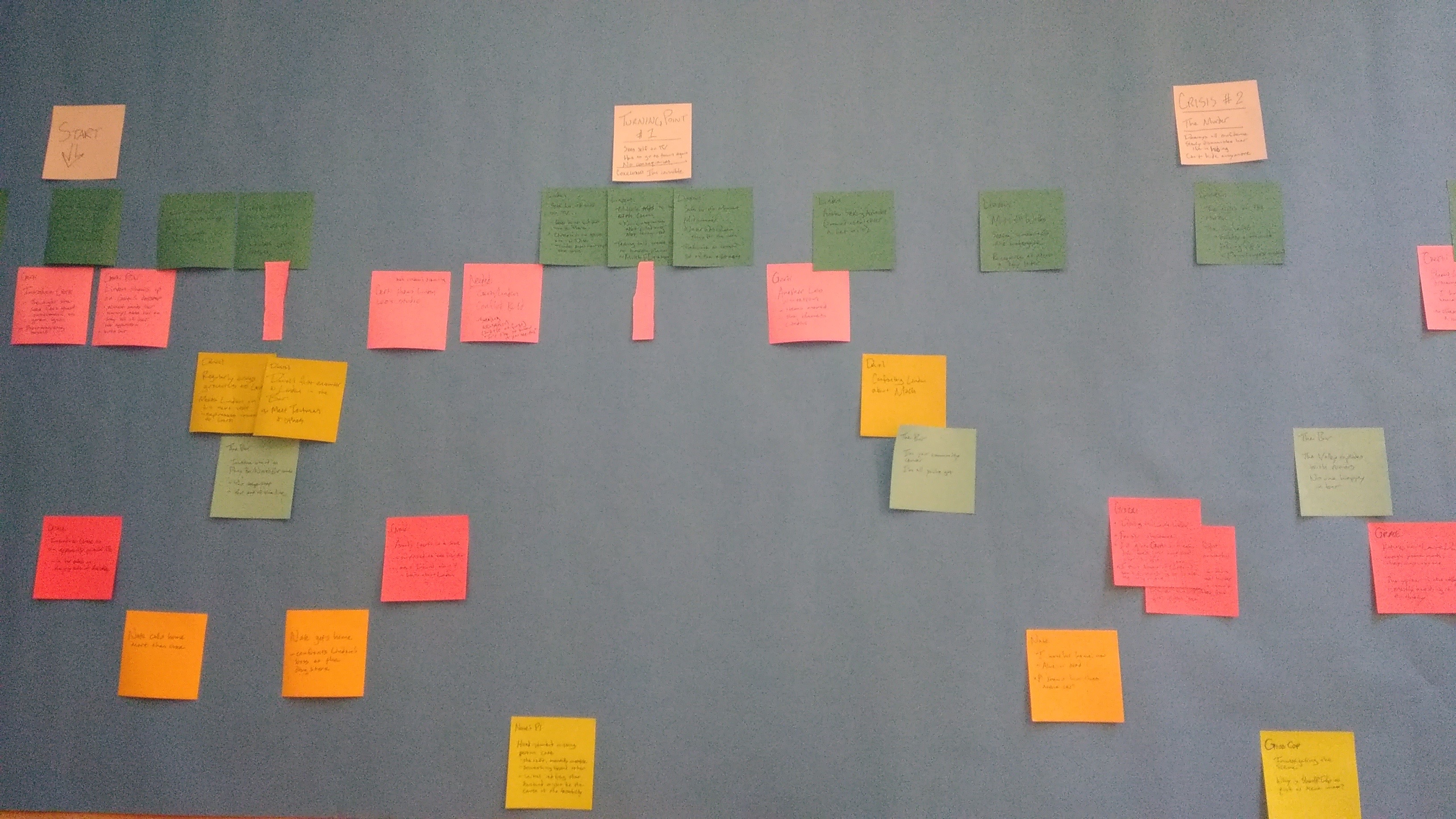

Some authors do this with vast excel spreadsheets. Some use a large whiteboard. I’m a fan of the giant sheet of bulletin board paper and sticky notes, color coded for each type of content. On each sticky note, I write a 3 to 5-word summary of a specific block of content or a file name. Then I begin to create a giant visual chart, moving the sticky notes from chapter to chapter, exploring how content could build, one thought upon another.

Sticky notes make it easy to move a section from one part of the book to another; I don’t have to erase and re-write the line item as I would on a whiteboard. When using the stickies in a color-coded fashion, I can also quickly see where there are gaps and where certain types of content are pooling: Oh look, all the good case stories are in Chapter 5 now, and there’s only one case story in Chapter 2.

Whatever tool you use, the goal is to establish a pattern and rhythm for your content. Particularly with instructional or informative books, it’s crucial that you develop a clear structure, so readers can build their knowledge base cleanly. This also helps them easily refer back to your book to find an important passage that they’d like to share with a friend.

Structure Example: Natural Health Books

The material often directs the structure—just as a jeweler might arrange an entire necklace around the large ornamental turquoise beads that are the focus of her piece. For example, when I ghostwrite natural health and wellness books, I often resort to an industry standard structure:

- 2-3 chapters describing the health challenge that is the focus of the book and explaining why current treatment strategies fall short

- 1-2 chapters providing an overview of new alternative approaches to the disease

- 6-8 chapters diving into specific alternative treatments that have the strongest scientific support, based on the author’s research and clinical practice

- 2-3 chapters describing how the reader can personalize their own lifestyle-based protocol based on this book’s advice

- Appendices providing charts, lab test recommendations, and follow-up resources

Every chapter is peppered with narrative examples, statistics, study summaries, and case studies. This “problem-solution” book structure is common and predictable. That’s not a bad thing; it’s a common structure because it works! It communicates smoothly and clearly, and that’s exactly what publishers want in this genre. Entrepreneurial inspiration and advice books often follow a similar problem-solution structure.

That structure is clean and simple. But there are as many approaches to book structure as there are authors! Everyone does it a little differently. Again, the material itself often drives the structure.

For instance, I’ve seen many informational and natural history books that arrange themselves around key interviews that the author conducted regarding a core topic—each chapter or over-arching section focuses on a new expert voice (i.e. Eager: The Surprising Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter, by Ben Goldfarb, as well as The Omnivore’s Dilemma by Michael Pollan).

I’ve also been reading in that new hybrid genre of Instructional/Self-help Memoir. In these books, each chapter begins with a personal story from the author’s life. That intimate memoir-style narrative is a launch pad to point out a key issue in the narrative and expound on it with statistics, expert interviews, and calls to action (i.e. How to Be An Anti-Racist by Ibram X. Kendi). This mix of story-sharing and hard news is incredibly effective as an instructional tool!

Try It!

Test drive the sticky note approach to organizing your book. For starters, recognize that this will take time! Organizing and revising takes as long as, or longer than, the draft-writing phase. So, allow a significant stretch of time for this task. It may take an entire full-time week or more simply to analyze your existing content and craft sticky note tags for each section in your book.

Once you’ve got your stack of sticky notes, begin arranging them on a spacious surface. A long sheet of bulletin board paper is especially useful because you can roll it out anywhere—on the floor, taped to a wall, flowing over a long folding table—and between sessions you can roll it up and set it aside.

Play. Move the sticky notes around. See how certain sections might build on each other. Notice where certain forms of content are getting bunched up and where they disappear. Adjust as needed.

Share your experience in the comments below.